Article 063 – What about seeing? Why we skip the most critical shooting mechanic.

Competition and the proliferation of challenging shooting standards have helped solidify the physical mechanics of shooting across the industry. The mechanics of shooting is simply physics and physics always wins. This is great; however, what about the visual and cognitive mechanics that matter more than physical shooting skills once we step off the range?

We recently wrote an article focused on law enforcement training. In it we use a simplified graphical model to explain why most police firearms training inhibits an officer’s ability to de-escalate at a synaptic level. We will not repeat that information here. We will simply summarize by stating that traditional police training methods construct neural circuitry without connective wiring to the mechanisms of de-escalation. It is a bit like building a car with no brake pedal—then wondering why the driver has trouble stopping.

In this article we want to back up a few paces and look at the broader issue of shooting mechanics, what is missing from them across the entire industry, and why.

Before we get into it, let’s make sure we are all on the same page with some foundational knowledge. Long-time readers, please bear with us for a few paragraphs.

First, it is critical to understand that when we develop long-term skills, the reason that retention happens is because we literally build physical structures (circuits) in the brain. These circuits work somewhat differently than the wiring and insulation in your home do, yet for our purposes here it is useful to think of them this way.

When we build a room, we run wires between a breaker box, switch, and light. This takes some effort; however, after we are done, we can easily turn the light on simply by flipping the switch to close the circuit.

In a similar manner, we construct neural circuits when we train. This process of circuit construction doesn’t happen instantly. However, through time and repetition, we can install wiring and insulation in our brains that enables us to retain skills and perform them effectively without conscious thought. Scientists now call this procedural memory consolidation. In the shooting world this concept has long been called the development of unconscious competence.

Training which is effective builds circuits. The question we pose here is simple: does it build the right circuitry for using guns in the real world?

During virtually all real-world encounters, a combination of context, the physical actions of the subject (or subjects), what tools they may or may not have, time, distance, and terrain are all going to determine a person’s actions. These factors will also be used to judge the actions of the participants after the fact.

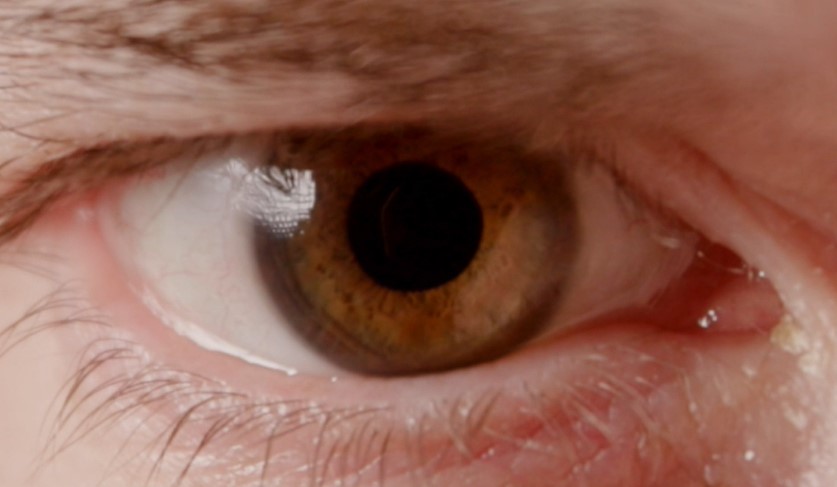

It is worth noting that most of these factors require seeing and evaluating complex and constantly changing stimuli within scene and terrain layouts—which often also change. It is further noteworthy that the seeing and evaluating required for effective tactical performance is best described as a continuous process, not a one-time event.

Imagine a batter in baseball deciding whether to swing during the pitcher’s windup—before the ball is even thrown—then cranking away with a swing regardless of what happens from that point forward. We would not expect much success from this batter.

We should expect even less success from ourselves during critical incidents if we do not have the necessary mechanisms in place to continue to evaluate what is happening around us throughout the course of an event. As the situation changes, we should change what we do in response—ideally using our actions to proactively shape our environments.

No reasonable person would claim we do this, or anything like it, during the overwhelming majority of firearms-related training. In most cases it does not happen at all. There is not even an evaluative process of any kind that occurs prior to shooting. In fact, we typically already know exactly what we are going to do before we ever get the stimulus (which is usually audible) that tells us to start doing it.

There are several obvious issues with this standard approach, most of which have been identified and criticized for decades. These include the predominant use of audible instead of visual stimulus to initiate action and the lack of target identification and decision-making before performing the shooting skill.

These things are important—certainly worthy of attention—and many trainers now are making valiant efforts to address them. Examples of common methods used to address these issues in whole or in part include turning targets, pop-up targets, turning targets with different stimulus (e.g., cell phone vs. pistol) stapled on each side, light boxes, etc.

However, these all could most accurately be described as preparatory mechanics, not shooting mechanics. Even during most successful efforts to address decision-making and visual processing during training, once the application of shooting mechanics (such as weapons presentation, visual references such as sight alignment and sight picture, trigger management, grip, and recoil management) are in play, the sequence of events is still frequently defined ahead of time and performed as if on-script (e.g., fire two rounds at the target, draw and fire four rounds in three seconds with the primary hand, etc.).

Returning to our question of circuitry: does the construction of neural circuitry for shooting that does NOT include continuously seeing and evaluating the subject during shooting produce the skills we need on the street? Could neural circuitry that does not include both seeing and processing the subject’s behavior as a part of the shooting mechanics even be defensible as a self-defense or law enforcement skill set?

The answer is both obvious and troublesome.

Obvious because once you know that skills during critical incidents are performed from the circuitry built through the training process that exists in long-term memory, it is impossible to make the case that performing physical mechanics in the absence of the visuomotor and information processing functions that are always required in the real world is building the right neural circuits. It clearly is not. It clearly cannot.

And, troublesome because almost every single one of us (the author included) has spent years working to build procedural circuits that are only about half relevant to what is needed in the real world—especially for domestic self-defense and law enforcement purposes.

As an industry, we learned to teach ourselves and our students to shoot. Granted, many folks still don’t do this well, but effective ways forward with sound training methods, techniques, and tactics are there for the taking. However, we never learned how to teach anyone how to see what was happening while they were shooting—at least outside of very high-resource environments.

Fixing this issue—for law enforcement officers in particular—is the training industry’s next big challenge.

Cowboy up.