The text of our prepared remarks from an April 11, 2018 speech to the annual FBI Firearms Instructor Conference and the FBI National Academy.

Thank you to the FBI, the FBI Academy, and the National Academy for the incredible opportunity to be here and speak with you all today. It is truly an honor.

Let me begin by telling you what I am not.

I am not an elite level competitive shooter. I don’t think anyone has ever accused me of not at least holding my own on any range, but I would be lying if I claimed some sort of “walk on water” personal skillset. I’m certainly not the best shooter in this room.

I am also not a former top tier military operator and I don’t have any special forces or special operations background. In the interest of full disclosure, I did attend BUD/S and quit in Hell Week—and my hat is perpetually off to anybody who makes it through that program, especially those who attend a winter class.

I also have no background in Law Enforcement.

So, this of course all begs the question, “Why is this guy even here?” Well, the best way to answer that is to tell a story.

As you might have seen in my bio, I graduated from the Naval Academy. And while there, I was the member of a small club sport that, at the time, was called the Combat Pistol Team.

Because of being on that team for four years, I had the opportunity to learn from some incredible mentors and advisors from the Marine Corps and Naval Special Warfare communities who happened to be stationed at the Academy.

This opportunity allowed me develop a real, professional-level of skill, especially with handguns, and also, because I functioned as the team’s training officer for my last two years, to gain experience setting up ranges, running ranges, and designing range-based training.

I graduated, spent a short time at BUD/S, and then went directly to the surface navy with something kind-of unique for a brand new junior officer. I had subject matter expertise in a technical skill.

For those who haven’t been in the military, normally the most valuable thing that a new junior officer hitting the fleet can know—is that they know absolutely nothing. And, of course, in every other area that was the case for me as well, but when it came to small arms and shooting skills, I not only had technical knowledge, I actually had technical knowledge that, for the most part, nobody else really had, which put me in a fairly unique position.

I entered the fleet just before the attack on the USS Cole happened. Prior to that attack, physical security and small arms skills just weren’t something that too many people took very seriously.

Nobody ever carried loaded guns and, in some cases, sailors wouldn’t even be issued bullets when they went on security watch, just a gun for show.

The standard training and qualification, if you were lucky enough to even get to fire a gun, was to have a gunner’s mate hand you a loaded gun when the ship was at sea. You fired five rounds, then handed the gun back to the gunner’s mate. If you hit the ocean, you passed.

After the Cole attack, the navy leadership decided they were going to take things a lot more seriously and, among other things, mandated that all guns carried on watch be loaded as of a certain date.

As the newly assigned gunnery officer on a navy frigate, that task fell to me.

I had somewhere around 200 people to train. And I had a number of weapons to train them on such as the Beretta, the Mossberg shotgun, and the M-14 rifle as well as larger, crew-served weapons such as the M2 .50 caliber machine gun.

After 4 years on the combat pistol team, I thought, “Hey, I know how to do this.” So I sketched out a training and qualification plan, then went right down the on-base range to block out several weeks of range time.

When the folks at the range finished laughing at me, they informed me that there wasn’t any available range time, not even on weekends, at least not until several months after the “load the guns” directive was to be implemented.

Then I looked at my ammunition allowance. I had enough in my initial annual ammo allotment to provide each sailor with approximately 10 rounds, enough for each person to shoot about 1/5 of the qualification course once per year.

No range availability. Not enough ammunition. Do these sound like familiar issues to anybody here?

So, I came up with a dry-fire program that I taught in the port side helo hanger twice a day.

Implementing, I had some challenges. I had to battle with some other members of the command’s leadership who didn’t fully support what I was doing.

I hounded leadership and individual sailors to get them to training.

I begged, borrowed and stole range time, mostly off base at civilian range, and pleaded with the navy for enough ammunition to support my training plan when I did have range time.

In the end, the result wasn’t what I wanted; I didn’t think it was good training, it was simply the best I could do with what I had.

When I left the ship, I got orders to report to the navy’s first mobile security squadron, as the operations officer for a security detachment.

Struggles there for resources, time, ammunition, ranges, etc. were plentiful as well; but, because of our security specific mission, I was able to set up something more like what we would still consider a weapons training package for my detachment, culminating with me teaching a six-day advanced weapons block for each team.

Then I realized something. We were not getting the “bang for the buck” that I thought we would.

It’s not that the sailors at mobile security weren’t generally better shooters than the sailors on the ship. They were.

But, the relative difference simply wasn’t that significant, especially when balanced against the amount of time, money and resources that the navy had invested.

To really grasp the significance here, it’s important to understand what those resources were.

First, most of the mobile security sailors were rated Master-at-Arms, which means that they were already fully trained, fully qualified, badged and sworn military police officers before they even came to the command.

Then, after arriving at the command, each sailor then went through all of the navy’s security and small arms schools.

Several had also completed the navy’s Small Arms Instructor program and were rated and billeted as small arms instructors at our command.

In addition, each of the sailors re-qualified with their weapons periodically to maintain their military police status, if I remember correctly that was every six months.

This means that the least amount of dedicated weapons training that each sailor had prior to coming to my “advanced” training block was 5 weeks.

Let me say that again. That’s 5 weeks of training dedicated solely to firearms training, nothing else.

That’s the least amount. Some of them had quite a bit more.

Yet, despite all of this investment in terms of time, money, ammunition, most of the sailors still didn’t even have a consistent grip on the pistol—which of course was their primary weapon as military police officers—when they showed up to my training block.

The lesson from this was, I thought, pretty clear—whatever it was we were doing, we were doing it wrong.

These experiences launched me on a personal mission to find a better way to do things—and to find out why a few hours of dryfire in a helicopter hanger with one range day was producing results that were not all that much different from those produced by 5 or more weeks of dedicated weapons training.

After I left the navy I went into overseas security consulting, which I did for quite a few years.

Working in the high-threat security industry gave me an opportunity to train with, operate with, work with, and supervise a wide variety of people from a wide variety of backgrounds, ranging from Tier 1 JSOC operators to citizens of third world countries with less than a third-grade education.

This gave me the opportunity to see first-hand how different backgrounds, different approaches to training, and different methods of training delivery not only impacted different people’s skills and the corresponding operational outcomes, but also how different methods of training and qualification impacted me personally in terms of my own skillset and operational performance.

Over those years, I tried to take these experiences and use them to and continue to evaluate and refine those the basic training methods that I used when I was on the ship.

I even tried taking the training into the commercial sector for the civilian market, working with now retired navy SEAL Larry Yatch, one of my best friends from the Academy, in a company we called Sealed Mindset.

Then, in early 2012, a friend of mine who also happened to be a neuroscience researcher was moving out to a rural area and asked me to do a self-defense shotgun course for her.

I was back working overseas at the time, but between deployments I were able to schedule a few days for the course and, while we weren’t able to fully apply the training methodology, (because of the time constraints) I was able to explain what the base program was and how it was supposed to work.

After we finished, her comment to me was that what I was doing was actually really cutting-edge in terms of the applied neuroscience research and she suggested that I look up a few subjects.

I did, and then set out to spend a few weeks and write a 10-15 page white paper on training methods.

As those kind of things tend to go sometimes, three years and 200 pages later I had learned a whole bunch of new stuff and had the work that I eventually published as the book Building Shooters.

So now I am coming back into the training side of the industry with a mission.

That mission is to drive a fundamental change in how we do things so we can get better results in training, better operational outcomes, reduce our liability, and do a better job working with the limited resources that are available to us.

I want to help the instructors, administrators and supervisors for what I call the “99%” of armed professionals.

There’s nothing wrong with the special forces, special-missions units folks. They are awesome, they do incredible things, and this stuff will benefit them too.

But more often than not, they have the resources they need to get the job done. If they need something, they get it.

It’s the rest of us who really are behind the power curve.

Because, let’s face it, the reality of the environment most of you in this room are in is that you have a really difficult job to do.

And to help you do it, you have training tools that don’t work, not enough time, not enough resources, and yet you’re still accountable for the outcomes.

This puts the people in this room in a bad position, because you have people you’re responsible for training and supervising and you currently have to go to them with something like this.

“A part of your job is literally life and death and jail time. Every time it comes up, those are the consequences. I’m not really going to teach you how to do it. I won’t help you learn how to do it on your own and I won’t give you access to the resources to learn how to do it on your own. But I will hold you accountable for it. Best of luck.”

While there is some hyperbole here, I think we can all general agree that this is pretty accurate.

Hopefully we can also all agree that this is, shall we say, a less than optimal situation for everybody.

This is the situation that I want to change in the industry,

And, I believe we have a way forward now to actually do it, and that is why I’m up here.I’m going keep it high-level today, but I want to into some detail both about what’s broken in the industry, and how we can fix it.

Let me ask a rhetorical question.

What do we do when stuff goes wrong?

For example, there’s a bad shoot, there’s a good shoot with bad publicity, there’s a negligent discharge, somebody gets killed or injured.

What do we do, systemically?

I’m outside the law enforcement community, but my public perception is that law enforcement does the same thing virtually everyone else in any industry does when things go wrong.

They circle the wagons where they can and then start pointing fingers at people or entities where they think they can reasonably assign the blame.

Now, just so there’s no confusion here, I’m personally a big believer in accountability, including accountability for individual people. Nothing I say here should be interpreted to detract from that.

However, I also think that, when it comes to use-of-force decision-making and the application of clinical tactical skills – or shooting people, hitting people, and cuffing people – that we, and I’m referring to society at large here, have gotten so caught up in the finger pointing game, that we’ve completely missed an 800lb gorilla hanging out in the room with us.

This gorilla is a series of significant and fundamental structural deficiencies that I refer to the two fundamental failures of the training industry.

Let me be clear. These aren’t failures of people. They are failures of infrastructure.

We fail in how we deliver training and we fail in how we measure successful outcomes.

I want you to keep these in the back of mind as the context for what we’re about to talk about.

Now let’s shift gears for a moment and let’s talk about the architecture and function of the human brain.

Why is this important?

Is it because everyone needs to turn into a psychology and neuroscience nerd to teach shooting and tactics? No.

It’s important because for us, and I’m collectively referring to us here as instructors in this field, our mission objective is to successfully put information into our student’s brains.

In other words, if we frame this in “tactical”, mission-planning terms, the brain of the student is literally the terrain that we fight on as instructors.

In an operational setting none of us would choose to go work in a place where we didn’t understand at least the basic terrain, or environment.

Allow me to suggest that we shouldn’t do it as instructors either.

Just like in operations, your chances of succeeding go way, way up if you know and understand the terrain you’re fighting on.

So, what I’m going to here is present a very simple model of how the brain works.

We aren’t going to get into the biological function or physical structures of the brain, instead we’re going to frame it as an information system.

And a disclaimer here, the human brain is the most complex system yet discovered in the Universe, I’m obviously not going to lay out its entire, detailed function here.

In fact, nobody could do that.

Even with all of our modern technology, brain research really is still in its infancy, we are just now beginning to have the tools to start trying to understand it.

I’m going to do is provide a model for understanding the practical, systems-level results of the processes that make-up brain function.

If you want to see the underlying science, it’s laid out in the bibliography of the book Building Shooters.

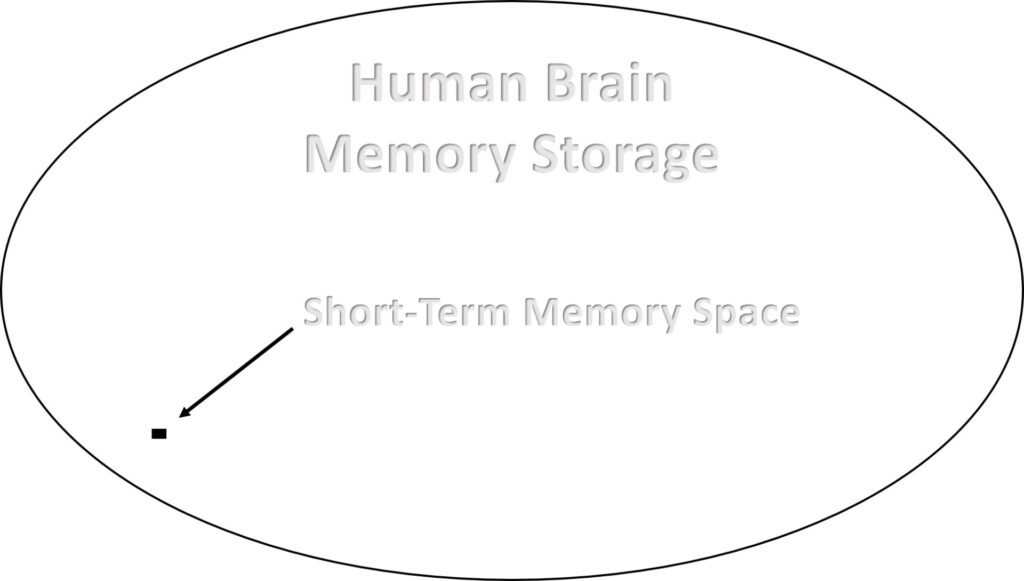

In our basic model there are three memory systems, which, if we use a computer analogy, you can think of as three separate hard drives.

They are short-term memory, long-term declarative memory, and long-term procedural memory.

From the perspective of function, short-term memory works kind of like RAM, or random access memory, in a computer.

For our purposes, this means that, while information comes and goes from this place, nothing gets stored there permanently.

Short-term memory is also really small. If we laid it out in comparison to the rest of the brain, it might look something like this.

**Image taken from Mentoring Shooters: The Gun Owner’s Guide to Building a Firearms Culture of Safety and Personal Responsibility

The next system is declarative memory. This is what we normally think of when we think of education and learning, because most of that is designed to get information here.

Again, using the computer analogy, this is like a 10 TB hard drive in the brain. It has lots and lots of storage space.

What’s unique about declarative memory is that it stores memory that is accessed consciously. In other words, you have to get what’s in it on purpose.

The last system is procedural memory. Much like declarative memory, this is a huge hard drive with virtually unlimited storage space.

However, the big difference is that procedural memory is a hard drive that only stores information that is accessed unconsciously.

In other words, you can’t really get to it on purpose, it is information that just comes out without you thinking about it.

Now here’s the thing, one of the very unique things about procedural memory is that it is the ONLY one of the three memory systems that you can get information out of during the stress response.

I’m sure all of you are familiar with the basics of the physiology of critical incidents.

Surprise, massive amounts of acute stress, shocking events, all of these things cause the body and brain to release a series of chemicals into the brain and bloodstream that change how things work.

This is sometimes called the sympathetic nervous system, and has some unique effects such as shaking, slowtime, and auditory exclusion.

Again, I expect that most people in here are intimately familiar with these things, mostly from first-hand experience.

One of the big “ah-ha” moments I had when researching this stuff is that the chemicals that dump into your brain during times of extreme stress actually act as a kind of “switch” – they trigger access to procedural memory and also preclude access to the rest of the brain.

So, from our perspective as trainers, let’s think about what this means to us.

I mentioned earlier that most of our educational research and method is intended to guide students towards getting information into their declarative memory systems – so they can be tested on it.

I actually would argue that most of our education and training structures are really designed more to make the information available to the student than they are to facilitate learning—then the student can learn it on their own if they put in the effort.

But, either way, the vast majority of what formal education and training programs do is try to put information into declarative memory.

That might be fine if you’re an accountant or analyst or something. For us, here’s the problem.

Even if the student learns everything, can perform all the skills flawlessly, and never forgets them, it might not matter all that much if they stored the information in the wrong memory system.

Sure, it works on the qual.

Everybody might even think this person is a really, really good shooter.

But still those skills might not be available in a gunfight.

Why? Because they’re stored in the wrong part of the brain.

The lesson here is simple. If we want it to happen during a critical incident, we need to put it here: in procedural memory.

So let’s talk about how to do that.

Let’s stick with a computer analogy.

When new information, by which I’m referring to just about anything—skills, knowledge, etc.—when new information goes into the brain the first thing that happens is that it hits a filter, we can think of it kind of like a firewall in this computer analogy.

It’s really important to understand that getting through this filter really is our first challenge as instructors—and that we fail to accomplish doing this all the time.

Anybody ever have a student not learn? Or that apparently learned something different than what you thought you taught them?

This might be part of why.

Once we get the information we want through the filter, it’s now in short-term memory.

There are a couple of things that are really important to understand about short-term memory.

We already know that it’s small, it has a very limited amount of storage space.

It also doesn’t store anything permanently.

You can have information in there, you can work with it while it’s in there and do stuff with it, like pass a qualification for instances, but this doesn’t mean that information is going to be retained.

What this means, is that if I’m going to put something new in, I first need to either push out something that’s already there or, alternatively, overwrite something that’s already there—which might end up corrupting both sets of information.

The last thing we need to know about procedural memory is that it appears to be compartmentalized, meaning that just because it can hold, say, 10 pieces of information, that doesn’t mean I can pick any 10 pieces of information and put those in.

Maybe I’ve got 10 slots for information, but I actually only have one space that will store visuomotor skills. And only one that will store “hand/tool” skills.

Let’s assume that’s true for this example.

This means that I can only put one visuomotor skill and one hand/tool skill into the brain at the same time.

I still have plenty of space in short-term memory, but I can’t put any more of these types of information into the brain.

So, recapping, the first thing that happens when we try to send information to the brain is that we hit a filter.

Once we finally get through the filter, we put the information into short-term memory.

And what do we know about short-term memory?

It’s really small, it’s compartmentalized, and it doesn’t store anything permanently.

This means that if we want our students to LEARN, it’s not enough to get the information here in short-term memory.

We need to make sure that the student’s brain transfers it to long-term memory, without it getting corrupted or lost.

As instructors in this field, we also know something else.

We know that if we want the information to be accessible in critical incident, we need to put it here….in the procedural memory system.

So, how do we do this?

During the research for Building Shooters I was able to identify 12 things that impact this process of transferring information into long-term procedural memory, which is often called consolidation.

Some of these things have a positive impact, some a negative impact.

They are explained in detail and the science is referenced in the book.

Here, I want to just talk about a few key points.

First, when we first present information to a student, it’s very difficult to know whether or not it will get through this natural “filter” in the brain.

Maybe it does, maybe it doesn’t.

What I’m going to propose to you today is—don’t worry about it.

Just expect they didn’t learn it the first time and then teach it again. This is called priming.

Literally teach the subject to the student with NO EXPECTATION that they will learn or retain it the first time they see it.

The purpose of this presentation isn’t to teach them. And it’s not to waste your time. Rather, it’s to let their brain’s filter recognize the information set when it sees it again, so it lets it pass into short-term memory.

So, principle one, prime first. Teach with no expectation of retention.

Second, account for the limitations of short-term memory.

The fact of the matter is that no matter how much information we are capable of teaching in the course of a day, the student’s ability to learn is limited by their brain function.

Consider this: when it comes to brand new material, you’re usually maxing out the student’s ability to learn in about 20 minutes, give or take.

This means that when teaching people who are completely new to firearms, you’re probably literally exceeding their biological capacity to learn new material by teaching them to load and unload the weapon in one day.

Think about that for a second.

If you’re maxing out the short-term memory system’s capacity in 20 minutes, what are you doing for the rest of an 8-hour training day?

Our basic model here tells us that you’re corrupting, overwriting, and replacing stuff.

This helps us get the information out as instructors, but it sure doesn’t help the student get the information in.

Certainly, when we are overwriting and corrupting most of what we teach people, especially the fundamentals, we aren’t setting them up for success. We’re doing the opposite.

Allow me to propose that we stop doing that.

Now, let me clarify something.

An 8 or more hour training day can be really valuable to a student—in the later forms of learning that occur AFTER the information is in long-term memory.

But, that type of training structure is not very useful for getting the information into long-term memory.

We prime first. Then, we teach—just as much information as we can put into short-term memory.

When we do, we do a lot of repetition so we as instructors can assure it’s the right information and so the brain knows the information is important and is worth storing.

Then we stop, and we let that information transfer into long-term memory.

One of the really interesting, and somewhat counter-intuitive, things I learned when I was doing the research is that an awful lot of this process happens subconsciously and that a lot of it can only happen when you’re NOT USING the information, AND some of it can only happen when you’re sleeping.

So if we want people to learn, after we’ve put the information successfully into short-term memory, we just need to leave it alone for a while, most of the science says about 24 hours, and we need to just let the students’ brains work through the biological processes necessary to move the information to long-term memory.

After it’s been moved?

Well, now we can’t corrupt it in short-term memory anymore, so we’re free to re-use this space with new data.

The last technique we’re going to talk about here is a concept that scientists call interleaved training. You can also think of this as chaotic learning.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the training session is in chaos, or completely unstructured.

What it means is that more of the brain that’s involved when you’re using a neural circuit that’s already in long-term memory, the more connected and important to the brain that circuit becomes.

For us this is important for two reasons.

First, it improves the chances that the information is placed into and being used in the procedural memory space. This means that it will be accessible during a critical incident.

Second, using these types of training methods allow us to build the same neurological machine in training that the students will need to use in the real world.

Let’s shift gears and talk about that for a second, because it brings us to our second fundamental failure—how and what we measure.

Building the right machine.

What “machine” do we use when we do most of our firearms training and qualification?

Let’s look at it.

In virtually all training and qualification we use a pre-known audio input feeding directly to a pre-known skill in declarative memory and (maybe) a pre-known visual input (detection of a specific, pre-known motion—turning target) to a pre-known skill in declarative memory.

Does this resemble what happens on the street?

No.

In the real world we have pre-existence of declarative knowledge (context) and stimuli in working/short-term memory (context), along with multiple potential skills that may be required in procedural memory. A combination of unknown audio and visual (combinations of object recognition and motion detection) inputs feed to pre-cognitive and cognitive processing centers. This information is then combined with context, fed to decision-making centers, linked with skills in procedural memory, then looped back to dynamic input from the visual (predominantly motion detection and object recognition) system and audio input system, which loops back through the processing and decision-making centers and back to skills in procedural memory.

It’s kind of like we teach and qualify people to use a riding lawnmower in the back yard, in preparation for driving a suburban out on the DC beltway during rush hour.

Does building, then measuring the first “machine”—to determine readiness for using the second, operational, “machine” make any real sense?

Does it help us assure good operational outcomes?

No.

Allow me to suggest that we should be both building and measuring the second machine.

Here’s another question.

We all have limited resources. What percentage of those resources do we put into the first machine?

For almost everyone in this room, I’m willing to bet the answer is “most of them.”

It might even be “all of them.”

So, when I talk about the two fundamental failures, this is what I mean.

We have talked just a little bit about how the brain works today, at a very high level.

When we take brain function and compare it against how we teach, how we measure our success in teaching, and how our measurement and qualification methods impact what we teach people to do, the gorilla in the room becomes pretty obvious.

We use a tool that doesn’t work to prepare the wrong machine to achieve a standard that doesn’t mean anything.

And then we wonder why we sometimes don’t get the results that we want on the street.

When things go wrong, it’s tempting to either point fingers or to point out limitations we have in terms of resources.

These issues may may have validity to them, but I submit to you that there are much more fundamental problems, structural problems, that exist with respect to our systemic training and qualifications.

There’s good news here though.

The good news is that we can fix it. We really can.

Before we break, let’s take just a minute to quickly look at what I believe and hope is going to be the future of the training industry.

First, we’re going to start basing the design of our training on the idea that what we’re really trying to do is create a series of neural networks.

While we can’t predict everything, we do pretty much know what we want those networks to be.

We know where in the brain we want the networks to be. And we know how to put them there, effectively and consistently.

So our training design and training structures will become more of an engineered training system that targets specific information to specific parts of the brain – by design.

Once we get information into the brain, we will then enhance and connect the relevant neural networks together—building the right machine, also by design.

On the measuring side, I believe we’re going to see significant change in two areas.

First, we’re going to stop measuring—by which I am referring to qualification— and therefore putting our focus of training effort on developing the wrong machine.

This doesn’t mean we will stop teaching or measuring fundamental shooting skills in parts of the training process.

It means that we start qualifying people by measuring them in ways that matter.

Instead of testing the wrong machine, we’re going to start building and measuring what I refer to as the Real Response that is required in the field.

Second, while we will always need some empirical measurements of student performance, they will become somewhat less important to the overall concept and process of training and qualification.

Instead, the emphasis will be on more of a QA/QC process around delivery of the engineered training programs that will create, connect, and enhance the neural networks that we know equate to successful operational performance.

In terms of results:

Once the industry as a whole starts making these changes, I think we’re going to start seeing greatly improved outcomes both in the field and in training.

And we might even see our overall costs and resource requirements go DOWN as well, because what we do now is so inefficient that most of our training time and resources are, in fact, wasted.

While all of this is still very early in terms of concept, much less implementation, I do have a few very early results I can share with you.

One is from the Division of Criminal Investigation Academy in South Dakota.

About 8 years ago, when all of this was still very much in its infancy, they started looking at restructuring their training program.

I had the opportunity early on to speak with their advanced training coordinator and they have incorporated a lot of the things we’ve talked about here today in terms of training design, as well as many other changes.

Before the changes, they averaged about a 12% failure rate in their firearms program. Now it’s down to less than 1%.

There’s another police academy, this one is in Arizona,

Just in the last few months they started implementing some changes based on some of these basic concepts.

They made just three simple changes.

First, they started priming and teaching most of their firearms skills in the classroom, dryfire, before taking students to the range.

Second, they intentionally made an effort to reduce the stress in firearms training by not sharing the qualification scores with the students.

They never even told them what a passing score was.

As an aside, this is based on some science that we haven’t talked about here today suggesting that the chemicals released into the brain by stress can often preclude effective learning during some stages of the learning process.

Third, they stopped emphasizing “zones” on the targets, and just told the students “do not miss the target” before each qualification.

That academy historically has seen about a 30% failure rate on qualifications in their firearms program.

Not as in 30% of students fail to pass the course, but about 30% of the total qualification courses fired during the program are failed.

During this last academy, after implementing just these small changes, their number of failures during the entire program went to zero.

Zero qualification failures by any student during the entire duration of the academy.

The bottom line is that this stuff works.

It doesn’t work because it’s based on artificial concepts, some pseudo-scientific mumbo jumbo, what policy makers would like to have happen, or some kind of mystical voodoo or secret sauce that I, or anybody else, invented.

It works because it’s based fundamentally around the capabilities and limitations of the human brain.

As trainers, this is the terrain we work in, and as operators, officers, or agents in the field, this is the control system for everything we do.

Once we start actually considering how the brain works and incorporating it into what we do, our outcomes can’t help but improve.

This concludes today’s prepared remarks. Thank you so much for your time and attention.

This speaking invitation does not include or imply endorsement of Building Shooters by the FBI, the FBI Academy, the FBI National Academy, or the United States Government. Attendance at this presentation was not required by the National Academy nor is it considered a part of the National Academy curriculum.