In the firearms and tactical training industry, most instructors are dedicated to what they do–because they genuinely care. Why? Because in this industry, if people ever have to do what they are being trained to do, if they fail, they die. Most instructors understand this and it shows through the effort they put into their training programs and teaching styles.

Unfortunately, many of these same caring, dedicated trainers often do as much harm as they do good for their students’ long-term performance potential. This isn’t due to malicious intent, nor is it due to incompetence, nor to apathy. Rather, this harm manifests simply from the use of training structures that are now considered the industry standard.

Consider the following example. I recently attended a defensive handgun training course at a local indoor range. Every student in the class was an existing gun owner and all students had previously received their carry permits, which requires that they attend an 8 hour training program and pass a shooting qualification. In addition, all but one of the other students had attended at least two “advanced” defensive shooting courses within the past six months, given by reputable and experienced local instructors. At the beginning of the class, the instructor prudently began with very simple weapon handling drills (such as loading and unloading) using dummy rounds in a classroom environment. Of the students in the class, I was the only student who was (initially) able to both load and unload his personally owned firearm confidently without instructor assistance.

In this real-life example, every student in the class had received at least 8 hours of previous handgun training. At least two of the students in the class had received over 24 hours of dedicated handgun training within the previous six months. And, yet, they struggled to even load their handguns without assistance. Is this because nobody ever showed them how to load their weapons or because the previous instructors were incompetent fools? Doubtful. More likely, these performance issues result from a simple lack of student retention.

Unfortunately, this situation is not uncommon–and it extends to every skill and technique that we, as firearms and tactical instructors, teach to our students. This isn’t necessarily because there’s something wrong with us, as trainers, rather it results from the methods of instruction and the approaches to training system design that are currently considered industry standard.

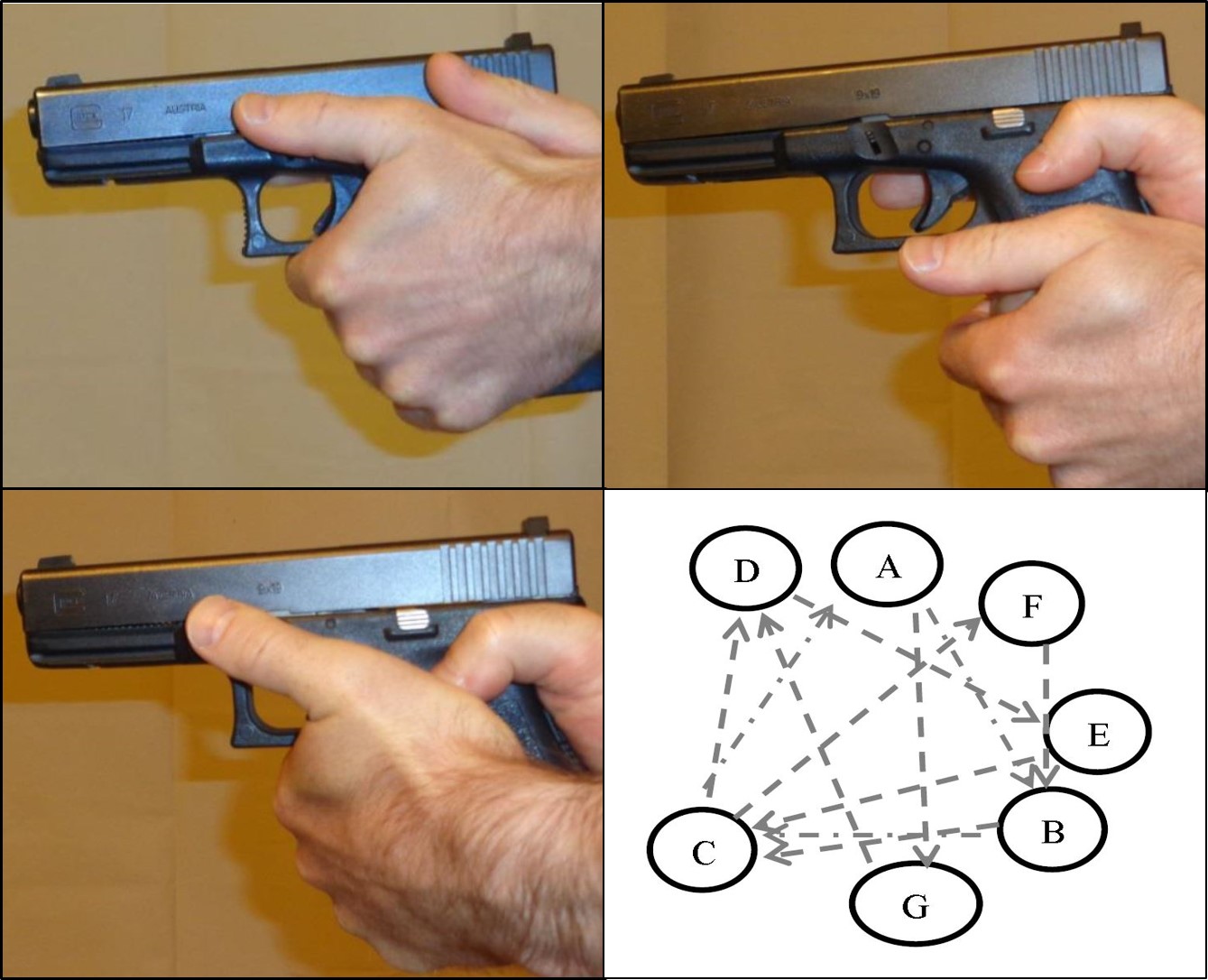

In February, 2006 I published an article in the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine titled “Bring Navy Small Arms Training to the Next Level.” In the article, I discuss the inadequacy of the Navy’s approach to small arms training at the time as it related to producing combat effective skills. One of the examples I used was my experience of running the sailors in my mobile security detachment through our advanced weapons training package, only to find that many of them did not have a consistent technique for gripping their handgun–holding it differently from one iteration of skill performance to the next.

To fully grasp the meaning of this, it is necessary to review the resources and time that had been expended by the Navy towards training these sailors in the use of small arms. First, most of the members of my detachment were rated Master-at-Arms, the Navy’s military police. This means that, prior to even being assigned to the command, these sailors had successfully completed military police training, including the military’s law enforcement weapons training and qualification program. After arriving at the command, each sailor then went through all of the Navy’s security and small arms schools (as they existed at the time). These consisted of the Armed Sentry Course (2 weeks), Shipboard Security Engagement Weapons (1 week), and Shipboard Security Engagement Tactics (1 week – no live fire). Then, all members of my detachment went through a 1 week weapons training package delivered by the U.S. Marine Corps, Weapons Training Battalion in Quantico, Virginia. A number of these sailors (who could not grip a pistol consistently) had also completed the Navy’s Small Arms Instructor program (SAMI) (2 weeks) and were rated and billeted as small arms instructors at our command. In addition, each of the sailors had re-qualified with their weapons while at the command on at least one occasion.

This experience begged the question. How could sailors who were qualified law enforcement officers (several of whom were also military qualified firearms instructors), each of whom had received up to six weeks of dedicated weapons training just within the previous six months, fail to possess the skill level necessary to perform a consistent grip on a handgun?

In these situations, as instructors, it is often tempting to assign blame to the student. After all, it was clearly not for a lack of instruction, range access, or opportunity that their skills were lacking. (Because, let’s face it, we taught them better–and we know that we taught them better.) Had this situation (the inability to perform a consistent grip on a handgun) been an isolated incident or two, it is possible that assigning blame to the student could even have been correct. However, when the majority of the detachment, to include some of the best overall performers, began the advanced training block with these same issues, there must have been another, primary, component to the problem.

These same types of issues, are something that I (and most other trainers I know) have seen consistently in trained and certified armed professionals over the past several decades. In fact, I recently had a well-known instructor tell me that he was considering leaving the industry because, in his words, “Most of the people who come to my classes are so screwed up [in terms of technical skill performance] that there’s really no way I can fix them.”

Since assigning blame to the students (at least in most cases) is both inaccurate and unproductive, it is equally tempting to shift fire and blame the instructor (assuming, of course, that the instructor wasn’t us). As Pat Morita’s Mr. Miyagi says in The Karate Kid, “There is no such thing as bad student, only bad teacher.” However, especially during organizationally driven training, the individual instructors are often severely limited in their ability to significantly impact the long-term outcomes produced in their students. Better instructors will produce better results; however, their capacity is often severely limited by the training infrastructure in use by the organization.

The fact of the matter is that our current industry accepted approach to training design and delivery is a significant contributor to the difficulty that trainers, even the great ones, have in delivering long-term retention and high levels of operational performance potential to students. This is especially true within the confines of the organizationally provided training infrastructure. There are many drawbacks to the current approach; one of the biggest (and the one that most significantly impacts students’ ability to build a long-term, sustainable skillset with respect to fundamentals such as handgun grip) is an effect that we call progressive interference.

Progressive interference occurs when repeated practice of a commonly performed complex skill (such as drawing a sidearm from a holster or performing an emergency reload or malfunction clearance) actually detracts from the student’s ability to perform the more fundamental skills that comprise components of the more complex skill. For example, a student cannot draw a handgun from the holster without gripping the handgun. There are other skills involved in drawing the weapon; however, gripping the weapon is itself a skill that is a fundamental component of a properly performed drawstroke.

When a student repeatedly draws the weapon from the holster, with a different grip being performed every time, this means that they literally are using different neural pathways that correspond to “grip.” Each time a different grip is performed, the brain’s ability to recognize and select the “correct” set of neural pathways that correspond to a proper grip becomes more difficult. This happens because when the brain goes to perform “grip,” and attempts to access the data that tells it how to perform the grip on a handgun, it sees a pile of data, all of it with the same name, “grip.” Imagine opening a file folder on your computer and looking for a document–and finding a list of documents with exactly the same file name. How would you know which one to open?

This is the situation that students’ brains are placed in when we use training methods that allow more than one “file” with the same name to exist in the brain. The brain can’t pick the “right” set of data, because there are too many sets of data, they are all named the same thing, they are relate to the same set of stimuli (in our example–the factors that result in drawing a sidearm), and there is no method of prioritization. Sometimes, the data may even become jumbled, with different parts of one data set overlapping and interfering with parts of another data set. It can be thought of (and in may ways is exactly like) a corrupted file on a computer drive. You can get the jist of what’s in the file, but it will never really look right.

So, how does this happen? Staying with our computer data metaphor, how do our students develop multiple files, containing different data but all with the same file name?

The simple answer is: Because we teach them that way.

More specifically, with respect to the progressive interference effect, we give them too much to learn in too short of a time period.

For example, as we document in our book Building Shooters, simply teaching a student to grip a handgun with a two handed grip meets the full capacity of the human brain’s ability to accept that type of new information into its “intake” system, also referred to as short-term memory. Nevertheless, we almost never stop there when we train. Usually, during the first training session, we also teach firearms safety, loading and unloading, trigger press, sight picture, recoil management, reloading, drawing from the holster and malfunction clearance. And we do it live fire. And that’s just before lunch…

As a result, the student’s brain never has the opportunity to process this new “file” (grip on a handgun), and move it into long-term memory–which is actually in a different geographical part of the brain. Because the “file” is still in an unstable form and still in short-term memory, it requires a conscious effort to access and perform correctly. Therefore, when other new skills, of which grip is a subcomponent, (such as drawing from the holster) are performed, the grip is often done with varying levels of incorrect technical performance.

Each time a different technical performance of the grip is done by the student, a new “file” is created. This file contains the same “name” (grip on a handgun) and is part of the same sequence (drawing from the holster–for example) as the original, technically correct file. However, the information contained in this new file is different. If enough different variations of the grip are performed, there could be around a dozen or so different “grip on a handgun” files cluttering the student’s brain by the end of the training day–many of which may be at least partially corrupted.

This is admittedly overstating things somewhat but, in some ways, it becomes almost irrelevant what the instructor is teaching or, in other words, how high quality the data is that’s in the original “file,” if the training system itself facilitates the student’s brain creating multiple, redundant, and technically incorrect variations of that original file, and stores them in the same place, with the same name, and links them to the same sequence(s) and set(s) of triggering stimuli. You can be the greatest instructor in the world, teaching the greatest techniques in the world–and it almost doesn’t matter. Your students can’t learn what you have to teach effectively. It’s not because there’s something wrong with what, or how, you’re teaching. It’s because the training system you are using literally not only stops the students from learning effectively, but actually corrupts the “data files” you are trying to deliver before they reach long-term memory.

The end result of progressive interference is that a great percentage of the training hours that we currently engage in are largely ineffective. In some ways, many of these training hours can even be considered to be counterproductive, assuming that the desired result is the development of technique that facilitates high-level performance potential.

Reversing this effect will require a new approach to training structure. Changing what or how we teach may be warranted in some cases; however, changing how we design and deliver training, especially at an organizational level, can reduce or eliminate the effects of progressive interference, thereby improving both the effectiveness and the efficiency of our training programs.