Author’s Note: Sometimes we all screw up; today was one of our days. The original version of this article contained a graph and reference to another trainer’s work. This was not presented to us as confidential material and was presented here in an effort to cite and give credit for exciting and complementary research. However, the trainers mentioned in the original article asked that we remove the graph and accompanying explanation as this article did not present the information within its original intended context. We have done so and replaced this with an original graph intended specifically for this purpose. We would ask any readers referencing this article to do the same and use the graph contained in this, current, version of the article. Our sincerest apologies to Dan Tolley and Ken Murray for this error.

One of the best parts about this experience of writing articles and publishing books (second one coming soon) is the interactions and feedback from readers, especially other trainers. There’s (of course) some of the inevitable internet cesspool stuff; however, most of the correspondence has been superb, leading to some great questions and interactions. We’re probably learning nearly as much as we are writing to be honest—lots of great stuff.

A recent email we received was from Rob Morse of Lake Charles, Louisiana (name used at his request) who has several of his own blogs at selfdefensegunstories.com and http://slowfacts.wordpress.com.

The text of his email is below:

Your book surprised me. I was watching a small child the other day. I contrast how he learned versus how you recommend we teach adults. The child certainly learned far more than he can retain in short-term memory. Was most of his time wasted? Then again, he will learn many of the same lessons again today. Is immersive education mostly wasted?

This was such a great question that we thought we would turn our response into an article.

First, a few explanations to help frame the discussion.

Immersive training environments are, well, what they sound like—immersive. The student is as completely engrossed in and surrounded by the subject matter as possible. In a perfect model, there are no real gaps. An example is language immersion training—students go to an environment where only the language they are trying to learn is used. Incidentally, as noted in Rob’s email, this is how young children learn. They are immersed in the world and everything is brand new.

In contrast, episodic learning consists of finite events and time-frames. A student attends, then they leave—often moving in to the next subject. This should sound familiar to every reader; it’s how schools are structured.

If you haven’t read our book Building Shooters, it outlines a lot of what is currently understood about the human brain’s functions related to both learning and applying things like motor skills and other tactically relevant functions. In it, we propose a simple modeling tool for training system design that is based around using what we know about the short-term memory system’s limitations and the factors that affect information retention to teach students in a surgically efficient, highly effective way. Because short-term memory is relatively small, and because (in our model) information must pass through short-term memory before it can be “learned,” teaching sessions at the beginning of a training program are very short and episodic, covering a very small amount of information.

With that background, here’s our (edited and expanded) response to the email:

There are a couple of things here. First, while the research we’ve done has not focused on childhood development (nor do we expect it to in the future—this is neither our interest nor particularly relevant to institutional tactical training), childrens’ brains function quite a bit differently than adults’ brains. This is especially true with respect to learning.

Many factors are involved, including significantly greater neuroplasticity. Small children may also be working in as much of a “cutting” mode as they are in a “building” mode with respect to neural function. In other words, their brains are eliminating fairly significant neural capability—based on lack of use. From a biological perspective, this makes the brain more efficient. If it’s not needed—it gets cut.

This explains, for example, why adults who have never been exposed to certain language sounds as children have extreme difficulty ever learning and pronouncing them, even after becoming otherwise fluent in a language. Their brains have “trimmed” the neurons that correspond with forming those sounds.

Second, Building Shooters frames a simplistic modeling tool (based on research and training experience) that is intended to explain and help predict the outcomes of incredibly complex processes. The specific numerical parameters associated with the short-term memory system’s limitations are not necessarily representative of every age, experience, IQ level, motor skill development level etc. (Note—this is articulated explicitly in the book, as is the potential need to adjust these parameters based on research with different demographics). Instead, these parameters are intended to be “middle of the strike zone” numbers based off our qualitative training observations.

With those things as a backdrop, we don’t think it’s necessarily fair to state that immersive learning experiences are “a waste of time.” In fact, it would not be wrong to characterize interleaved training as immersive learning. (Note—if you’re not familiar with this, here’s a recent article we wrote about it.)

We do, however, think it’s fair to say that immersive learning experiences (at least at the beginning of the training process) are inefficient with respect to skillsets that require technical skill performance, especially when those technical skills are progressive in nature. (Note—progressive skills are defined for our purposes as skills of which other skills are subcomponents. For example, three subcomponents of weapons presentation to engage a target are grip, trigger management, and recoil management.)

There’s also a difference between the “during” and “end of training period” performance ability (what the industry typically measures and uses as benchmarks), and long-term retention. In fact, this is one of the most critical points behind the development of our approach to training system design.

Sure, you can get people to people perform relatively high levels of skill in response to specific stimuli within a blocked training period. However, information extinction following these types of training experiences is pretty severe. This may be fine for decent test scores. It’s not so fine for critical incident performance at some unknown future date and time.

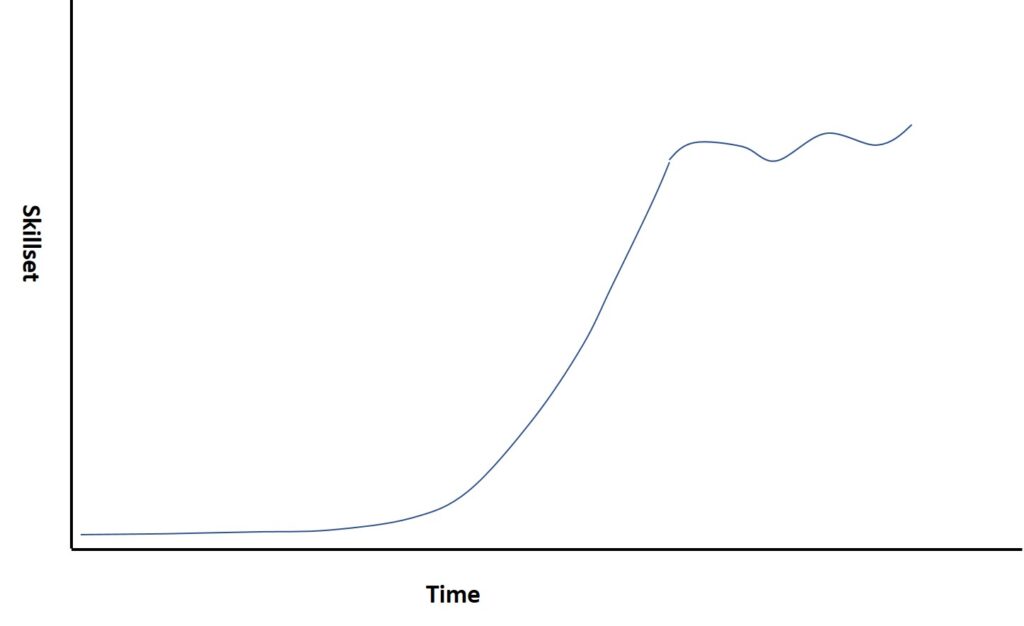

When a training system is designed using our modeling tool, the results are roughly approximated by the picture below.

(Please Note– This picture was created with a quick sketch in .ppt just for this article. It’s conceptual, not a plotted graph based on real data.)

This graph represents a more or less logarithmic progression of a student’s skillset, until the skillset itself reaches maturity through training limitations, time limitations, student interest, conflicting time requirements etc. At this point, in theory, perishable skillsets should alternately decay and improve as they are practiced or not, while the entire skillset of the individual continues to slowly improve with operational experience.

While this may or may not actually be mathematically accurate, consider for this discussion that the area under the curve is the volume of consolidated skills. (Consolidation is a component of learning. After consolidation occurs, information is no longer as at risk to corruption through unfocused/improper performance.)

At the beginning of the training process, the area under the curve is virtually zero—as is the volume of the student’s skillset. An immersive environment that requires technical skill performance can potentially be harmful to the student here, because of the effects of progressive interference. At the early stages of training, it’s possible for immersive training methods to actually prolong the time period required for students to develop long-term, technically correct skill performance.

It’s also possible that immersion in technical skills very early on could prevent the procedural consolidation of optimal technique performance from occurring it all. And, if stress and scenario-based training are involved, it could perhaps even contribute to some stress related neurological trauma. This could result from (among other things) creating an unnecessary anxiety response to specific stimuli in high-stress, scenario-based environments.

(Note—we believe that serious academic research is needed here. More and more evidence is suggesting that we may be hurting people (neurologically) in training—due to suboptimal design.)

There’s another consideration too. When students start to develop an extensive procedural neural map, they start working with new information via its relationship to the existing data in long-term memory rather than treating it like it’s brand new. While our model for development doesn’t include explicit acknowledgement of this effect—the effect does occur.

At a certain point in training, (probably around the break-over point) it appears that students start bypassing short-term memory for a lot of learning. But, in order to get there effectively (and, in an institutional setting, consistently and predictably), the students’ brains must have enough information consolidated into long-term memory for the new material to associate and connect with.

Once the student’s skillset begins to rocket upward—now an immersive environment becomes extremely productive–basically it’s interleaved training as discussed in the book.

It is important to note here that immersive training will probably only provide significant operational benefits if it is truly immersive. Purely immersing the student in discrete skill performance (such as drawing a handgun for time, or repeatedly burning plate racks) isn’t actually immersive for any operational purpose. These things can be very fun and are not without value—we’re not knocking them. However, they are just continued exposure to (and perhaps enhancement of) a discreet skill in a blocked, sterile training environment—not immersion.

All of this being said, immersive training can work well and produce competent and skilled students. We know this because it has—and does.

Especially as applied to institutional settings, however, the question becomes, “At what cost?”

First off, real immersive training for firearms and tactics is pretty rare outside of a few very special, highly selective places. However, let’s pretend that our current approaches are actually immersive.

If (numbers below are purely for example purposes—not actual suggestions of training hours) an institution invests 40 man-hours of training for a result they could have equally achieved (or probably even improved upon) with only 20 man-hours had they simply used a different delivery structure, the opportunity for improvement, savings, or both is self-evident.

Also, let’s assume (again, numbers are made up just for example) an institution recruits and on-boards 100 trainees for every 70 armed professionals they eventually hire. Let’s further assume (because it’s probably true) that some significant percentage of those 70 new-hires are barely competent (or worse) in their armed skillset upon completing training. This is using the existing, industry standard, training structures.

Now, what if using different training structures could change these results? What if graduation rates could be significantly improved? What if people who are operational liabilities could be more easily identified and dismissed, and both the armed professional skillsets and resultant operational performance could be greatly improved? What if costs can even be cut in the process?

If some (or all) of those things can happen, doesn’t shifting training structures make sense?

At BUILDING SHOOTERS, we believe all of this is possible. The industry just needs to start understanding what happens in the students’ brains when we teach them, and start training people the same way that they actually learn. It is time to start looking at maximizing efficiency and improving the rate of return on our investments with respect to work-force development in the armed professions.